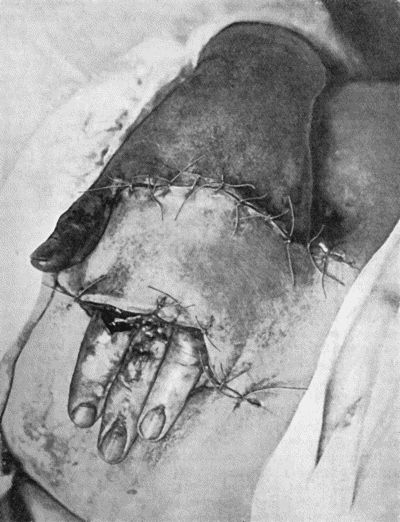

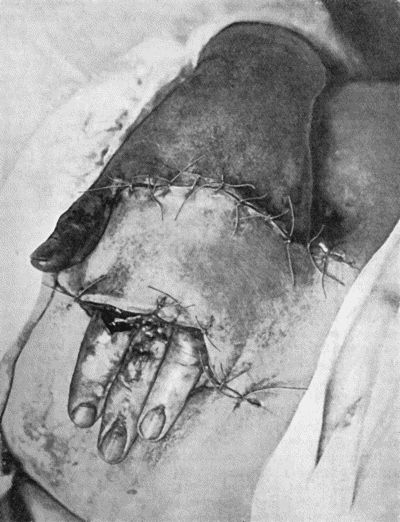

Fig. 1.—Ulcer of back of Hand covered by flap of skin raised from anterior abdominal wall. The lateral edges of the flap are divided after the graft has adhered.

The Blood lends itself in an ideal manner to transplantation, or, as it has long been called, transfusion. Being always a homoplastic transfer, the new blood is not always tolerated by the old, in which case biochemical changes occur, resulting in hæmolysis, which corresponds to the disintegration of other unsuccessful homoplastic grafts. (See article on Transfusion, Op. Surg., p. 37.)

The Skin.—The skin was the first tissue to be used for grafting purposes, and it is still employed with greater frequency than any other, as lesions causing defects of skin are extremely common and without the aid of grafts are tedious in healing.

Skin grafts may be applied to a raw surface or to one that is covered with granulations.

Skin grafting of raw surfaces is commonly indicated after operations for malignant disease in which considerable areas of skin must be sacrificed, and after accidents, such as avulsion of the scalp by machinery.

Skin grafting of granulating surfaces is chiefly employed to promote healing in the large defects of skin caused by severe burns; the grafting is carried out when the surface is covered by a uniform layer of healthy granulations and before the inevitable contraction of scar tissue makes itself manifest. Before applying the grafts it is usual to scrape away the granulations until the young fibrous tissue underneath is exposed, but, if the granulations are healthy and can be rendered aseptic, the grafts may be placed on them directly.

If it is decided to scrape away the granulations, the oozing must be arrested by pressure with a pad of gauze, a sheet of dental rubber or green protective is placed next the raw surface to prevent the gauze adhering and starting the bleeding afresh when it is removed.

Methods of Skin-Grafting.—Two methods are employed: one in which the epidermis is mainly or exclusively employed—epidermis or epithelial grafting; the other, in which the graft consists of the whole thickness of the true skin—cutis-grafting.

Epidermis or Epithelial Grafting.—The method introduced by the late Professor Thiersch of Leipsic is that almost universally practised. It consists in transplanting strips of epidermis shaved from the surface of the skin, the razor passing through the tips of the papillæ, which appear as tiny red points yielding a moderate ooze of blood.

The strips are obtained from the front and lateral aspects of the thigh or upper arm, the skin in those regions being pliable and comparatively free from hairs.

They are cut with a sharp hollow-ground razor or with Thiersch's grafting knife, the blade of which is rinsed in alcohol and kept moistened with warm saline solution. The cutting is made easier if the skin is well stretched and kept flat and perfectly steady, the operator's left hand exerting traction on the skin behind, the hands of the assistant on the skin in front, one above and the other below the seat of operation. To ensure uniform strips being cut, the razor is kept parallel with the surface and used with a short, rapid, sawing movement, so that, with a little practice, grafts six or eight inches long by one or two inches broad can readily be cut. The patient is given a general anæsthetic, or regional anæsthesia is obtained by injections of a solution of one per cent. novocain into the line of the lateral and middle cutaneous nerves; the disinfection of the skin is carried out on the usual lines, any chemical agent being finally got rid of, however, by means of alcohol followed by saline solution.

The strips of epidermis wrinkle up on the knife and are directly transferred to the surface, for which they should be made to form a complete carpet, slightly overlapping the edges of the area and of one another; some blunt instrument is used to straighten out the strips, which are then subjected to firm pressure with a pad of gauze to express blood and air-bells and to ensure accurate contact, for this must be as close as that between a postage stamp and the paper to which it is affixed.

As a dressing for the grafted area and of that also from which the grafts have been taken, gauze soaked in liquid paraffin—the patent variety known as ambrine is excellent—appears to be the best; the gauze should be moistened every other day or so with fresh paraffin, so that, at the end of a week, when the grafts should have united, the gauze can be removed without risk of detaching them. Dental wax is another useful type of dressing; as is also picric acid solution. Over the gauze, there is applied a thick layer of cotton wool, and the whole dressing is kept in place by a firmly applied bandage, and in the case of the limbs some form of splint should be added to prevent movement.

A dressing may be dispensed with altogether, the grafts being protected by a wire cage such as is used after vaccination, but they tend to dry up and come to resemble a scab.

When the grafts have healed, it is well to protect them from injury and to prevent them drying up and cracking by the liberal application of lanoline or vaseline.

The new skin is at first insensitive and is fixed to the underlying connective tissue or bone, but in course of time (from six weeks onwards) sensation returns and the formation of elastic tissue beneath renders the skin pliant and movable so that it can be pinched up between the finger and thumb.

Reverdin's method consists in planting out pieces of skin not bigger than a pin-head over a granulating surface. It is seldom employed.

Grafts of the Cutis Vera.—Grafts consisting of the entire thickness of the true skin were specially advocated by Wolff and are often associated with his name. They should be cut oval or spindle-shaped, to facilitate the approximation of the edges of the resulting wound. The graft should be cut to the exact size of the surface it is to cover; Gillies believes that tension of the graft favours its taking. These grafts may be placed either on a fresh raw surface or on healthy granulations. It is sometimes an advantage to stitch them in position, especially on the face. The dressing and the after-treatment are the same as in epidermis grafting.

There is a degree of uncertainty about the graft retaining its vitality long enough to permit of its deriving the necessary nourishment from its new surroundings; in a certain number of cases the flap dies and is thrown off as a slough—moist or dry according to the presence or absence of septic infection.

The technique for cutis-grafting must be without a flaw, and the asepsis absolute; there must not only be a complete absence of movement, but there must be no traction on the flap that will endanger its blood supply.

Owing to the uncertainty in the results of cutis-grafting the two-stage or indirect method has been introduced, and its almost uniform success has led to its sphere of application being widely extended. The flap is raised as in the direct method but is left attached at one of its margins for a period ranging from 14 to 21 days until its blood supply from its new bed is assured; the detachment is then made complete. The blood supply of the proposed flap may influence its selection and the way in which it is fashioned; for example, a flap cut from the side of the head to fill a defect in the cheek, having in its margin of attachment or pedicle the superficial temporal artery, is more likely to take than a flap cut with its base above.

Another modification is to raise the flap but leave it connected at both ends like the piers of a bridge; this method is well suited to defects of skin on the dorsum of the fingers, hand and forearm, the bridge of skin is raised from the abdominal wall and the hand is passed beneath it and securely fixed in position; after an interval of 14 to 21 days, when the flap is assured of its blood supply, the piers of the bridge are divided (Fig. 1). With undermining it is usually easy to bring the edges of the gap in the abdominal wall together, even in children; the skin flap on the dorsum of the hand appears rather thick and prominent—almost like the pad of a boxing-glove—for some time, but the restoration of function in the capacity to flex the fingers is gratifying in the extreme.

Fig. 1.—Ulcer of back of Hand covered by flap of skin raised from anterior abdominal wall. The lateral edges of the flap are divided after the graft has adhered.

The indirect element of this method of skin-grafting may be carried still further by transferring the flap of skin first to one part of the body and then, after it has taken, transferring it to a third part. Gillies has especially developed this method in the remedying of deformities of the face caused by gunshot wounds and by petrol burns in air-men. A rectangular flap of skin is marked out in the neck and chest, the lateral margins of the flap are raised sufficiently to enable them to be brought together so as to form a tube of skin: after the circulation has been restored, the lower end of the tube is detached and is brought up to the lip or cheek, or eyelid, where it is wanted; when this end has derived its new blood supply, the other end is detached from the neck and brought up to where it is wanted. In this way, skin from the chest may be brought up to form a new forehead and eyelids.

Grafts of mucous membrane are used to cover defects in the lip, cheek, and conjunctiva. The technique is similar to that employed in skin-grafting; the sources of mucous membrane are limited and the element of septic infection cannot always be excluded.

Fat.—Adipose tissue has a low vitality, but it is easily retained and it readily lends itself to transplantation. Portions of fat are often obtainable at operations—from the omentum, for example, otherwise the subcutaneous fat of the buttock is the most accessible; it may be employed to fill up cavities of all kinds in order to obtain more rapid and sounder healing and also to remedy deformity, as in filling up a depression in the cheek or forehead. It is ultimately converted into ordinary connective tissue pari passu with the absorption of the fat.

The fascia lata of the thigh is widely and successfully used as a graft to fill defects in the dura mater, and interposed between the bones of a joint—if the articular cartilage has been destroyed—to prevent the occurrence of ankylosis.

The peritoneum of hydrocele and hernial sacs and of the omentum readily lends itself to transplantation.

Cartilage and bone, next to skin, are the tissues most frequently employed for grafting purposes; their sphere of action is so extensive and includes so much of technical detail in their employment, that they will be considered later with the surgery of the bones and joints and with the methods of re-forming the nose.

Tendons and blood vessels readily lend themselves to transplantation and will also be referred to later.

Muscle and nerve, on the other hand, do not retain their vitality when severed from their surroundings and do not functionate as grafts except for their connective-tissue elements, which it goes without saying are more readily obtainable from other sources.

Portions of the ovary and of the thyreoid have been successfully transplanted into the subcutaneous cellular tissue of the abdominal wall by Tuffier and others. In these new surroundings, the ovary or thyreoid is vascularised and has been shown to functionate, but there is not sufficient regeneration of the essential tissue elements to “carry on”; the secreting tissue is gradually replaced by connective tissue and the special function comes to an end. Even such temporary function may, however, tide a patient over a difficult period.