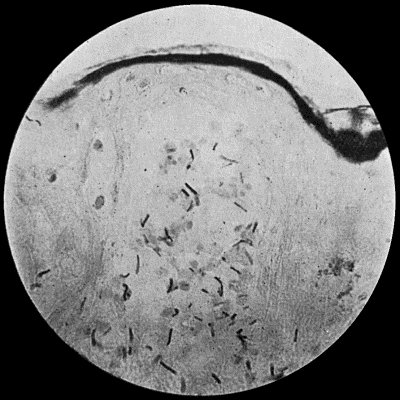

Fig. 27.—Bacillus of Anthrax in section of skin, from a case of malignant pustule; shows vesicle containing bacilli. × 400 diam. Gram's stain.

Anthrax is a comparatively rare disease, communicable to man from certain of the lower animals, such as sheep, oxen, horses, deer, and other herbivora. In animals it is characterised by symptoms of acute general poisoning, and, from the fact that it produces a marked enlargement of the spleen, is known in veterinary surgery as “splenic fever.”

The bacillus anthracis (Fig. 27), the largest of the known pathogenic bacteria, occurs in groups or in chains made up of numerous bacilli, each bacillus measuring from 6 to 8 µ in length. The organisms are found in enormous numbers throughout the bodies of animals that have died of anthrax, and are readily recognised and cultivated. Sporulation only takes place outside the body, probably because free oxygen is necessary to the process. In the spore-free condition, the organisms are readily destroyed by ordinary germicides, and by the gastric juice. The spores, on the other hand, have a high degree of resistance. Not only do they remain viable in the dry state for long periods, even up to a year, but they survive boiling for five minutes, and must be subjected to dry heat at 140° C. for several hours before they are destroyed.

Fig. 27.—Bacillus of Anthrax in section of skin, from a case of malignant pustule; shows vesicle containing bacilli. × 400 diam. Gram's stain.

Clinical Varieties of Anthrax.—In man, anthrax may manifest itself in one of three clinical forms.

It may be transmitted by means of spores or bacilli directly from a diseased animal to those who, by their occupation or otherwise, are brought into contact with it—for example, shepherds, butchers, veterinary surgeons, or hide-porters. Infection may occur on the face by the use of a shaving-brush contaminated by spores. The path of infection is usually through an abrasion of the skin, and the primary manifestations are local, constituting what is known as the malignant pustule.

In other cases the disease is contracted through the inhalation of the dried spores into the respiratory passages. This occurs oftenest in those who work amongst wool, fur, and rags, and a form of acute pneumonia of great virulence ensues. This affection is known as wool-sorter's disease, and is almost universally fatal.

There is reason to believe that infection may also take place by means of spores ingested into the alimentary canal in meat or milk derived from diseased animals, or in infected water.

Clinical Features of Malignant Pustule.—We shall here confine ourselves to the consideration of the local lesion as it occurs in the skin—the malignant pustule.

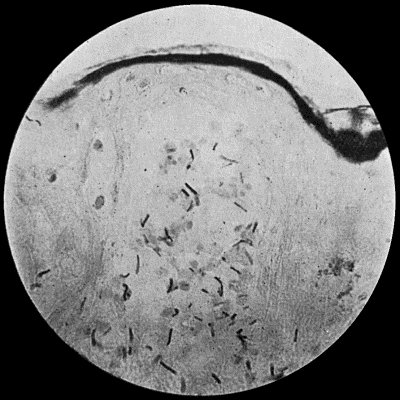

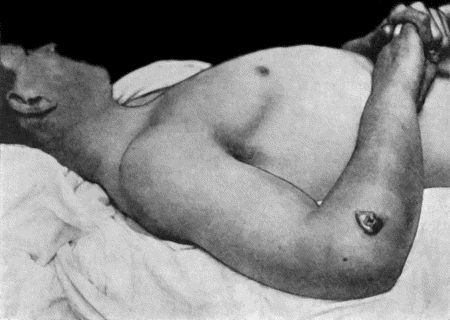

The point of infection is usually on an uncovered part of the body, such as the face, hands, arms, or back of the neck, and the wound may be exceedingly minute. After an incubation period varying from a few hours to several days, a reddish nodule resembling a small boil appears at the seat of inoculation, the immediately surrounding skin becomes swollen and indurated, and over the indurated area there appear a number of small vesicles containing serum, which at first is clear but soon becomes blood-stained (Fig. 28). Coincidently the subcutaneous tissue for a considerable distance around becomes markedly œdematous, and the skin red and tense. Within a few hours, blood is extravasated in the centre of the indurated area, the blisters burst, and a dark brown or black eschar, composed of necrosed skin and subcutaneous tissue and altered blood, forms (Fig. 29). Meanwhile the induration extends, fresh vesicles form and in turn burst, and the eschar increases in size. The neighbouring lymph glands soon become swollen and tender. The affected part is hot and itchy, but the patient does not complain of great pain. There is a moderate degree of constitutional disturbance, with headache, nausea, and sometimes shivering.

If the infection becomes generalised—anthracæmia—the temperature rises to 103° or 104° F., the pulse becomes feeble and rapid, and other signs of severe blood-poisoning appear: vomiting, diarrhœa, pains in the limbs, headache and delirium, and the condition proves fatal in from five to eight days.

Differential Diagnosis.—When the malignant pustule is fully developed, the central slough with the surrounding vesicles and the widespread œdema are characteristic. The bacillus can be obtained from the peripheral portion of the slough, from the blisters, and from the adjacent lymph vessels and glands. The occupation of the patient may suggest the possibility of anthrax infection.

Fig. 28.—Malignant Pustule, third day after infection with Anthrax, showing great œdema of upper extremity and pectoral region (cf. Fig. 29).

Fig. 29.—Malignant Pustule, fourteen days after infection, showing black eschar in process of separation. The œdema has largely disappeared. Treated by Sclavo's serum (cf. Fig. 28).

Prophylaxis.—Any wound suspected of being infected with anthrax should at once be cauterised with caustic potash, the actual cautery, or pure carbolic acid.

Treatment.—The best results hitherto obtained have followed the use of the anti-anthrax serum introduced by Sclavo. The initial dose is 40 c.c., and if the serum is given early in the disease, the beneficial effects are manifest in a few hours. Favourable results have also followed the use of pyocyanase, a vaccine prepared from the bacillus pyocyaneus.

By some it is recommended that the local lesion should be freely excised; others advocate cauterisation of the affected part with solid caustic potash till all the indurated area is softened. Gräf has had excellent results by the latter method in a large series of cases, the œdema subsiding in about twenty-four hours and the constitutional symptoms rapidly improving. Wolff and Wiewiorowski, on the other hand, have had equally good results by simply protecting the local lesion with a mild antiseptic dressing, and relying upon general treatment.

The general treatment consists in feeding and stimulating the patient as freely as possible. Quinine, in 5 to 10 grain doses every four hours, and powdered ipecacuanha, in 40 to 60 grain doses every four hours, have also been employed with apparent benefit.