Fig. 130.—Syphilitic Disease of Skull, showing a sequestrum in process of separation.

Syphilitic affections of bone may be met with at any period of the disease, but the graver forms occur in the tertiary stage of acquired and inherited syphilis. The virus is carried by the blood-stream to all parts of the skeleton, but the local development of the disease appears to be influenced by a predisposition on the part of individual bones.

Syphilitic diseases of bone are much less common in practice than those due to pyogenic and tuberculous infectious, and they show a marked predilection for the tibia, sternum, and skull. They differ from tuberculous affections in the frequency with which they attack the shafts of bones rather than the articular ends, and in the comparative rarity of joint complications.

Evanescent periostitis is met with in acquired syphilis during the period of the early skin eruptions. The patient complains, especially at night, of pains over the frontal bone, ribs, sternum, tibić, or ulnć. Localised tenderness is elicited on pressure, and there is slight swelling, which, however, rarely amounts to what may be described as a periosteal node.

In the later stages of acquired syphilis, gummatous periostitis and osteomyelitis occur, and are characterised by the formation in the periosteum and marrow of circumscribed gummata or of a diffuse gummatous infiltration. The framework of the bone is rarefied in the area immediately involved, and sclerosed in the parts beyond. If the gummatous tissue degenerates and breaks down, and especially if the overlying skin is perforated and septic infection is superadded, the bone disintegrates and exhibits the condition known as syphilitic caries; sometimes a portion of bone has its blood supply so far interfered with that it dies—syphilitic necrosis. Syphilitic sequestra are heavier and denser than normal bone, because sclerosis usually precedes death of the bone. The bones especially affected by gummatous disease are: the skull, the septum of the nose, the nasal bones, palate, sternum, femur, tibia, and the bones of the forearm.

In the bones of the skull, gummata may form in the peri-cranium, diploë, or dura mater. An isolated gumma forms a firm elastic swelling, shading off into the surroundings. In the macerated bone there is a depression or an actual perforation of the calvaria; multiple gummata tend to fuse with one another at their margins, giving the appearance of a combination of circles: these sometimes surround an area of bone and cut it off from its blood supply (Fig. 130). If the overlying skin is destroyed and septic infection superadded, such an isolated area of bone is apt to die and furnish a sequestrum; the separation of the dead bone is extremely slow, partly from the want of vascularity in the sclerosed bone round about, and partly from the density of the sequestrum. In exceptional cases the necrosis involves the entire vertical plate of the frontal bone. Pus is formed between the bone and the dura (suppurative pachymeningitis), and this may be followed by cerebral abscess or by pyćmia. Gummatous disease in the wall of the orbit may cause displacement of the eye and paralysis of the ocular muscles.

On the inner surface of the skull, the formation of gummatous tissue may cause pressure on the brain and give rise to intense pain in the head, Jacksonian epilepsy, or paralysis, the symptoms varying with the seat and extent of the disease. The cranial nerves may be pressed upon at the base, especially at their points of exit, and this gives rise to symptoms of irritation or paralysis in the area of distribution of the nerves affected.

In the septum of the nose, the nasal bones, and the hard palate, gummatous disease causes ulceration, which, beginning in the mucous membrane, spreads to the bones, and being complicated with septic infection leads to caries and necrosis. In the nose, the disease is attended with stinking discharge (ozœna), the extrusion of portions of dead bone, and subsequently with deformity characterised by loss of the bridge of the nose; in the palate, it is common to have a perforation, so that the air escapes through the nose in speaking, giving to the voice a characteristic nasal tone.

Syphilitic disease of the tibia may be taken as the type of the affection as it occurs in the long bones. Gummatous disease in the periosteum may be localised and result in the formation of a well-defined node, or the whole shaft may become the seat of an irregular nodular enlargement (Fig. 132). If the bone is macerated, it is found to be heavier and bulkier than normal; there is diffuse sclerosis with obliteration of the medullary canal, and the surface is uneven from heaping up of new bone—hyperostosis (Fig. 131). If a periosteal gumma breaks down and invades the skin, a syphilitic ulcer is formed with carious bone at the bottom. A central gumma may eat away the surrounding bone to such an extent that the shaft undergoes pathological fracture. In the rare cases in which it attacks the articular end of a long bone, gummatous disease may implicate the adjacent joint and give rise to syphilitic arthritis.

Clinical Features.—There is severe boring pain—as if a gimlet were being driven into the bone. It is worst at night, preventing sleep, and has been ascribed to compression of the nerves in the narrowed Haversian canals.

The periosteal gumma appears as a smooth, circumscribed swelling which is soft and elastic in the centre and firm at the margins, and shades off into the surrounding bone. The gumma may be completely absorbed or it may give place to a hard node. In some cases the gumma softens in the centre, the skin becomes adherent, thin, and red, and finally gives way. The opening in the skin persists as a sinus, or develops into a typical ulcer with irregular, crescentic margins; in either case a probe reveals the presence of carious bone or of a sequestrum. The health may be impaired as a result of mixed infection, and the absorption of toxins and waxy degeneration in the viscera may ultimately be induced.

A central gumma in a long bone may not reveal its presence until it erupts through the shell and reaches the periosteal surface or invades an adjacent joint. Sometimes the first manifestation is a fracture of the bone produced by slight violence.

In radiograms the appearance of syphilitic bones is usually characteristic. When there is hyperostosis and sclerosis, the shaft appears denser and broader than normal, and the contour is uneven or wavy. When there is a central gumma, the shadow is interrupted by a rounded clear area, like that of a chondroma or myeloma, but there is sclerosis round about.

Diagnosis.—The conditions most liable to be mistaken for syphilitic disease of bone are chronic staphylococcal osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, and sarcoma; and the diagnosis is to be made by the history and progress of the disease, the result of examination with the X-rays, and the results of specific tests and treatment.

Treatment.—The general health is to be improved by open air, by nourishing food, and by the administration of cod-liver oil, iron, and arsenic. Anti-syphilitic remedies should be given, and if they are administered before there is any destruction of tissue, the benefit derived from them is usually marked.

Radiograms show the rapid absorption of the new bone both on the surface and in the marrow, and are of value in establishing the therapeutic diagnosis.

In certain cases, and particularly when there are destructive changes in the bone complicated with pyogenic infection, specific remedies have little effect. In cases of persistent or relapsing gummatous disease with ulceration of skin, it is often necessary to remove the diseased soft parts with the sharp spoon and scissors, and to gouge or chisel away the unhealthy bone, on the same lines as in tuberculous disease. When hyperostosis and sclerosis of the bone is attended with severe pain which does not yield to blistering, the periosteum may be incised and the sclerosed bone perforated with a drill or trephine.

Lesions of Bone in Inherited Syphilis.—Craniotabes, in which the flat bones of the skull undergo absorption in patches, was formerly regarded as syphilitic, but it is now known to result from prolonged malnutrition from any cause. Bossing of the skull resulting in the formation of Parrot's nodes is also being withdrawn from the category of syphilitic affections. The lesions in infancy—epiphysitis, bossing of the skull, and craniotabes—have been referred to in the chapter on inherited syphilis.

Epiphysitis or Syphilitic Perichondritis.—The first of these terms is misleading, because the lesion involves the ossifying junction and the shaft of the bone, and the epiphysis only indirectly. The young bone is replaced by granulation tissue, so that large clear areas are seen with the X-rays. The symptoms are referred to the joint, because it is there that the muscles are inserted and drag on the perichondrium when movement occurs; swelling is most marked in the vicinity of the joint, and it may be added to by effusion into the synovial cavity. The baby, usually under six months, is noticed to be feverish and fretful and to cry when touched. The mother discovers that the pain is caused by moving a particular limb, usually the arm, as the humerus, radius, and ulna are the bones most commonly affected; the limb, moreover, hangs useless at the side as if paralysed, and the condition was formerly described as syphilitic pseudo-paralysis.

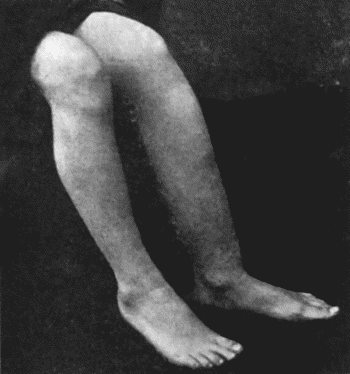

The lesions met with later correspond to those of the tertiary period of the acquired disease, but as they affect bones which are still actively growing, the effects are more striking. Gummatous disease may come and go over periods of many years, with the result that the external appearance and architectural arrangement of a long bone come to be profoundly altered. In the tibia, for example, the shaft is bowed forward in a gentle curve, which is compared to the curve of a sabre—“sabre-blade” deformity (Fig. 132). The diffuse thickening all round the bone obscures the sharp margins so that the bone becomes circular in section and the anterior and mesial edges are blunted, and the comparison to a cucumber is deserved. In some cases the tibia is actually increased in length as well as in girth.

Fig. 132.—Sabre-blade Deformity of Left Tibia in Inherited Syphilis.

(From a photograph lent by Sir George T. Beatson.)

The contrast between the grossly enlarged and misshapen tibia and the normal or even attenuated fibula is a striking one.

Treatment is carried out on lines similar to those recommended in the acquired disease. When curving of the tibia causes disability in walking, the bone may be straightened by a cuneiform resection.

Syphilitic dactylitis is met with chiefly in children. It may affect any of the fingers or toes, but is commonest in the first phalanx of the index-finger or of the thumb. Several fingers may be attacked at the same time or in succession. The lesion consists in a gummatous infiltration of the soft parts surrounding the phalanx, or a gummatous osteomyelitis, but there is practically no tendency to break down and discharge, or to the formation of a sequestrum as is so common in tuberculous dactylitis.

The finger becomes the seat of a swelling, which is more evident on the dorsal aspect, and, according to the distribution and extent of the disease, it is acorn-shaped, fusiform, or cylindrical. It is firm and elastic, and usually painless. The movements are impaired, especially if the joints are involved. In its early stages the disease is amenable to anti-syphilitic treatment, and complete recovery is the rule.