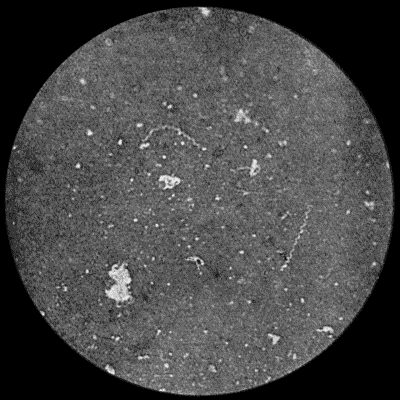

Fig. 36.—Spirochæta pallida from scraping of hard Chancre of Prepuce. × 1000 diam. Burri method.

Syphilis is an infective disease due to the entrance into the body of a specific virus. It is nearly always communicated from one individual to another by contact infection, the discharge from a syphilitic lesion being the medium through which the virus is transmitted, and the seat of inoculation is almost invariably a surface covered by squamous epithelium. The disease was unknown in Europe before the year 1493, when it was introduced into Spain by Columbus' crew, who were infected in Haiti, where the disease had been endemic from time immemorial (Bloch).

The granulation tissue which forms as a result of the reaction of the tissues to the presence of the virus is chiefly composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells, along with an abundant new formation of capillary blood vessels. Giant cells are not uncommon, but the endothelioid cells, which are so marked a feature of tuberculous granulation tissue, are practically absent.

When syphilis is communicated from one individual to another by contact infection, the condition is spoken of as acquired syphilis, and the first visible sign of the disease appears at the site of inoculation, and is known as the primary lesion. Those who have thus acquired the disease may transmit it to their offspring, who are then said to suffer from inherited syphilis.

The Virus of Syphilis.—The cause of syphilis, whether acquired or inherited, is the organism, described by Schaudinn and Hoffman, in 1905, under the name of spirochæta pallida or spironema pallidum. It is a delicate, thread-like spirilla, in length averaging from 8 to 10 µ and in width about 0.25 µ, and is distinguished from other spirochætes by its delicate shape, its dead-white appearance, together with its closely twisted spiral form, with numerous undulations (10 to 26), which are perfectly regular, and are characteristic in that they remain the same during rest and in active movement (Fig. 36). In a fresh specimen, such as a scraping from a hard chancre suspended in a little salt solution, it shows active movements. The organism is readily destroyed by heat, and perishes in the absence of moisture. It has been proved experimentally that it remains infective only up to six hours after its removal from the body. Noguchi has succeeded in obtaining pure cultures from the infected tissues of the rabbit.

The spirochæte may be recognised in films made by scraping the deeper parts of the primary lesion, from papules on the skin, or from blisters artificially raised on lesions of the skin or on the immediately adjacent portion of healthy skin. It is readily found in the mucous patches and condylomata of the secondary period. It is best stained by Giemsa's method, and its recognition is greatly aided by the use of the ultra-microscope.

The spirochæte has been demonstrated in every form of syphilitic lesion, and has been isolated from the blood—with difficulty—and from lymph withdrawn by a hollow needle from enlarged lymph glands. The saliva of persons suffering from syphilitic lesions of the mouth also contains the organism.

In tertiary lesions there is greater difficulty in demonstrating the spirochæte, but small numbers have been found in the peripheral parts of gummata and in the thickened patches in syphilitic disease of the aorta. Noguchi and Moore have discovered the spirochæte in the brain in a number of cases of general paralysis of the insane. The spirochæte may persist in the body for a long time after infection; its presence has been demonstrated as long as sixteen years after the original acquisition of the disease.

In inherited syphilis the spirochæte is present in enormous numbers throughout all the organs and fluids of the body.

Considerable interest attaches to the observations of Metchnikoff, Roux, and Neisser, who have succeeded in conveying syphilis to the chimpanzee and other members of the ape tribe, obtaining primary and secondary lesions similar to those observed in man, and also containing the spirochæte. In animals the disease has been transmitted by material from all kinds of syphilitic lesions, including even the blood in the secondary and tertiary stages of the disease. The primary lesion is in the form of an indurated papule, in every respect resembling the corresponding lesion in man, and associated with enlargement and induration of the lymph glands. The primary lesion usually appears about thirty days after inoculation, to be followed, in about half the cases, by secondary manifestations, which are usually of a mild character; in no instance has any tertiary lesion been observed. The severity of the affection amongst apes would appear to be in proportion to the nearness of the relationship of the animal to the human subject. The eye of the rabbit is also susceptible to inoculation from syphilitic lesions; the material in a finely divided state is introduced into the anterior chamber of the eye.

Attempts to immunise against the disease have so far proved negative, but Metchnikoff has shown that the inunction of the part inoculated with an ointment containing 33 per cent. of calomel, within one hour of infection, suffices to neutralise the virus in man, and up to eighteen hours in monkeys. He recommends the adoption of this procedure in the prophylaxis of syphilis.

Noguchi has made an emulsion of dead spirochætes which he calls luetin, and which gives a specific reaction resembling that of tuberculin in tuberculosis, a papule or a pustule forming at the site of the intra-dermal injection. It is said to be most efficacious in the tertiary and latent forms of syphilis, which are precisely those forms in which the diagnosis is surrounded with difficulties.